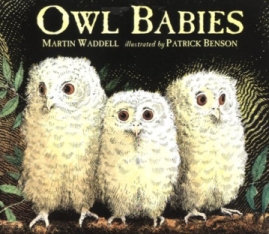

It is mid-morning and the classroom is buzzing with the steady hum of open work time. Three-year-old Hannah is at work at the atelier. She is drawing a plan for the owl she is going to build in the block area. The drawing has triangular shapes and tight parallel scribbles . “I made an owl. It look like a beak. I am going to make it speak.” Then she gets to work, building the owl from blocks, fitting several triangular pieces so that they poke jauntily up from her construction.

When I see the drawing later, beside a photograph of the finished construction I have taken for upcoming curriculum night, Hannah’s owl does speak – and the message is powerful. After a mere three years of experience in this world, she is capable of an incredible feat: the ability to take a purely abstract concept and recreate it in the solid material world. This ability to conjure and then construct, to imagine and then to realize, is the ability we call creativity.

Creativity has received much attention in the field of education lately. Sir Ken Robinson, head of the British government’s 1998 advisory committee on creative and cultural education, is something of a creativity expert. After all, he was knighted in 2003 for his achievements as the leader of a wide body of research on the significance of creativity in the education system. He makes a simple point: the majority of students in our current education system are failing at achieving successful lives and careers because, all over the world, cognitive and academic abilities are valued over creativity. I encourage you to pay a visit to TED.com to learn more more about Sir Ken Robinson’s brilliant work.

What does educational neuroscience have to say on the subject of creativity? Dr. Paul Howard-Jones, a leading expert in the role of neuroscience in educational practice and policy, has conducted ground-breaking research over the last ten years in neuroscience, (Howard-Jones et al 2005); developmental psychology, (Howard-Jones, Taylor and Sutton, 2002); and neuroeducation (Howard-Jones, 2002), identifying ways to use new scientific understanding of creativity to form strategies for fostering creativity in the classroom. In 2008, Howard-Jones and his team began a large-scale project in the UK to co-construct an understanding of creativity in education that draws on neuropsychological concepts. The results were presented in a publication titled Fostering creative thinking: co-constructed insights from neuroscience and education. You can download a pdf of this publication in Neuroeducational Rescources.

The publication asks a key question, one that I have set out to explore this year. Given that creativity is recognized as a capacity vital to a student’s success and should be treated as such in the classroom: Can creativity be taught, and if so, how?

Howard-Jones presents some clean facts, well-supported by quality neuroscience findings, on fostering creativity in the classroom. I would like to review these against the backdrop of the Reggio-inspired arts curricula that have developed in my own classroom this year.

1. Finding the creative balance

We’ve just arrived back from the playground, and my students are choosing their work for the morning. We’ve begun something new in the blocks this week. Instead of simply asking children who choose the Block Area what they are going to build, teachers are inviting children to draw a picture of their rocket ship, racetrack, seahorse and rain forest first. Detailed drawings emerge at the atelier table, with lines and shapes that convey direction and movement. Students eagerly offer descriptions about the parts of their blueprints, the height, size and angles of the constructions in their mind. It is their own idea to bring their plans into the block area with them. Some revisit the plan as they work, others build directly on top of their drawings.

We’ve just arrived back from the playground, and my students are choosing their work for the morning. We’ve begun something new in the blocks this week. Instead of simply asking children who choose the Block Area what they are going to build, teachers are inviting children to draw a picture of their rocket ship, racetrack, seahorse and rain forest first. Detailed drawings emerge at the atelier table, with lines and shapes that convey direction and movement. Students eagerly offer descriptions about the parts of their blueprints, the height, size and angles of the constructions in their mind. It is their own idea to bring their plans into the block area with them. Some revisit the plan as they work, others build directly on top of their drawings.

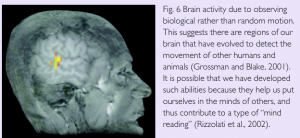

According to Howard-Jones, one way that teachers may play a pivotal role in the fostering of creative thought is by supporting a child in learning to move between modes of generative and analytical thinking as they engage in creative activity and projects. We know now, in both neuroscience and education, that ideas of the Left/Right brain being divided respectively into logical and creative are outdated and misunderstood. Hot spots of activity in the brain appear all over a scan taken during a creative task. Recent research (Howard-Jones et al, 2005) used fMRI to look at the brains of subjects as they were engaged in creative story generation. A key finding was the way that the type of thinking varied between freely generating ideas and connections, and then returning to analytical assessment of the story so far. In other words, the process of purposeful creativity involves frontal areas that are associated with conscious control.

According to Howard-Jones, one way that teachers may play a pivotal role in the fostering of creative thought is by supporting a child in learning to move between modes of generative and analytical thinking as they engage in creative activity and projects. We know now, in both neuroscience and education, that ideas of the Left/Right brain being divided respectively into logical and creative are outdated and misunderstood. Hot spots of activity in the brain appear all over a scan taken during a creative task. Recent research (Howard-Jones et al, 2005) used fMRI to look at the brains of subjects as they were engaged in creative story generation. A key finding was the way that the type of thinking varied between freely generating ideas and connections, and then returning to analytical assessment of the story so far. In other words, the process of purposeful creativity involves frontal areas that are associated with conscious control.

Supporting creativity in very young children is a controversial topic. There has been much debate on the necessity of the teacher’s role. Children are already so creative naturally, isn’t it best to just stand back and let them have free, sensory experiences? Yet, it is clear to me that even my young students are able to employ both of these modes of thought during a creative project. The drawing, planning and and discussion ends up being as much a part of the process as the making. Beginning block building at the atelier table becomes a welcome habit, and the different kinds of constructions happening in the block area swell as new children seek the experience of building their drawings. Themes that began in childrens’ stories and artwork now have a new form of expression. Documentation panels cover the walls in the blocks, showing childrens’ plans beside their finished constructions.

Supporting creativity in very young children is a controversial topic. There has been much debate on the necessity of the teacher’s role. Children are already so creative naturally, isn’t it best to just stand back and let them have free, sensory experiences? Yet, it is clear to me that even my young students are able to employ both of these modes of thought during a creative project. The drawing, planning and and discussion ends up being as much a part of the process as the making. Beginning block building at the atelier table becomes a welcome habit, and the different kinds of constructions happening in the block area swell as new children seek the experience of building their drawings. Themes that began in childrens’ stories and artwork now have a new form of expression. Documentation panels cover the walls in the blocks, showing childrens’ plans beside their finished constructions.

The planning and reflective aspect of creative work is at the heart of the Reggio approach, and the art that comes from these preschools has deeply affected the whole world. The traveling exhibit, The Hundred Languages of Children, presents the quality of art that can be achieved when children plan, reflect and revisit their work. The resulting art is rich, complex, and imbued with layer upon layer of experience. I feel this stands as a strong testament to the need to encourage children at a young age to involve their whole brain in the creative process.

2. Modeling creativity

2. Modeling creativity

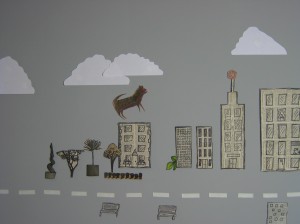

Our atelierista, Kristen, is working in the Blue Room this morning, and children are watching intently as she spreads out various printed images, transparencies and translucent tracings on the rug. Today each child will take a turn in the atelier with her, beginning their own sculpture from cardboard and a variety of found objects. First, she is presenting her idea. This idea, of an artistic presentation, represents a collaboration between her approach and ours. The presentation is adapted from the Montessori approach, and is a foundation of our teaching approach. Using careful language, motions and concrete materials, Kristen is going to present the day’s project by modeling her own creative process in the creation of a massive painting – the maps of two cities. (It was considered a happy coincidence that we had been studying maps in the Blue Room for the past two weeks. These kinds of connections just have a way of happening in a creative preschool classroom!)

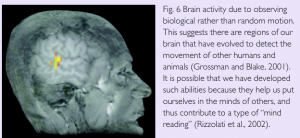

The intriguing piece of neuroscience that backs up the Montessori presentation is perhaps the most fascinating finding of the last ten years, at least for me: the mirror neuron system (Rizzolati et al, 2002). From a small lab in Italy, the country where the Reggio Emila preschools were born, comes the finding that watching another human conduct a goal-directed action lights up the very same areas in a human cortex as actually performing the action. This mirror-neuron system resides in the motor planning areas of our cortex, and reminds us that much of our higher consciousness as humans comes from experiencing others’ action as our own. In other words, the work of the hands speaks volumes.

The intriguing piece of neuroscience that backs up the Montessori presentation is perhaps the most fascinating finding of the last ten years, at least for me: the mirror neuron system (Rizzolati et al, 2002). From a small lab in Italy, the country where the Reggio Emila preschools were born, comes the finding that watching another human conduct a goal-directed action lights up the very same areas in a human cortex as actually performing the action. This mirror-neuron system resides in the motor planning areas of our cortex, and reminds us that much of our higher consciousness as humans comes from experiencing others’ action as our own. In other words, the work of the hands speaks volumes.

I would venture that my students took information from the way Kristen’s hands moved when handling and explaining her plans that they could have never received through language alone. Howard-Jones contends that modeling creativity is a key element of teaching the creative process. Body language, facial expressions, spoken expression and concrete materials give students an embodied experience of the creative process, as well as a respect for those who provide it.

Again, this is a controversial topic. It has in fact taken Kristen a little time to get comfortable with modeling her own creativity before our young and impressionable students. Will it skew their work, will make them want to copy her rather than chart their own course? I have stood firm that seeing the creative process is vital for the children. Something happens when my young students witness her process. It is something intangible, something about the expression on her face and the care she takes with her plan papers – a reverence and respect for her own work. This unspoken respect for the artistic process infuses the childrens’ work in the atelier as they sketch their ideas on graph paper, point carefully to the parts of their plans, gather materials from the shelves – and sit patiently, holding pieces of cardboard together while they dry.

3. Seeing is creating

Sculptures are displayed on shelves in the atelier and block area, and tacked beside them are the plans on graph paper. Many sculptures are mothers – Mommy, mommy, and mommy in a yellow dress. Others are princess castles, or rocket ships, or race tracks. Adeline, age three, has titled her sculpture, The Building in my Mind. The plans hanging in the atelier are matched by other plans all over the Blue Room. On the wall of the Block Area are childrens’ drawings, Hannah’s owl among them, hanging beside photographs of finished block constructions. The Dramatic Play area, a subway station this month, is full of maps that children have drawn to guide their play. The remarkable finding is the same for all areas of the classroom: guiding our children to visualize ahead of time what they are going to make, build or even play allows them to hold onto their idea – and create it – with rich detail and language.

Sculptures are displayed on shelves in the atelier and block area, and tacked beside them are the plans on graph paper. Many sculptures are mothers – Mommy, mommy, and mommy in a yellow dress. Others are princess castles, or rocket ships, or race tracks. Adeline, age three, has titled her sculpture, The Building in my Mind. The plans hanging in the atelier are matched by other plans all over the Blue Room. On the wall of the Block Area are childrens’ drawings, Hannah’s owl among them, hanging beside photographs of finished block constructions. The Dramatic Play area, a subway station this month, is full of maps that children have drawn to guide their play. The remarkable finding is the same for all areas of the classroom: guiding our children to visualize ahead of time what they are going to make, build or even play allows them to hold onto their idea – and create it – with rich detail and language.

A major change is happening to the brains of my students as they turn three, a change that will forever set them apart from the rest of the animal species: the ability to create their own reality in the world based on an internal vision. I do not know if there is anything so fascinating as watching this ability develop in children. I am constantly reminded of human evolution – of the majesty of the earliest cave paintings and carved figurines of the human form.

According to Howard-Jones, mental visualization provides the leap from the concrete to the abstract. As humans, our frontal lobes have the ability to see something that is not yet there and then create it. As the frontal lobes develop in children, they acquire the ability, around age three, to remember, to sustain and manipulate information, to use imagination to create concrete miracles one can look at and hold in the hand.

The interplay of the concrete and the abstract are very important at this time in development. The abstract is grounded in the concrete, and the concrete communicates the abstract. The most important and earth changing realizations began as a picture in someone’s mind – from planets revolving around a bright sun to electrons orbiting an atomic nucleus. Art is the method through which we communicate these ideas to other human beings when language will not suffice.

To plan and then to make is the work of the human being – creativity. Yet, it is not an easy feat. As teachers, we are responsible for providing an environment where creativity can blossom. This is no longer just for the happiness of our students within the classroom – the creative ability is what is going to sustain and support our students in the future that awaits them after we are gone.

To plan and then to make is the work of the human being – creativity. Yet, it is not an easy feat. As teachers, we are responsible for providing an environment where creativity can blossom. This is no longer just for the happiness of our students within the classroom – the creative ability is what is going to sustain and support our students in the future that awaits them after we are gone.

In summary, fostering creativity requires teaching the intricacies of the creative process, modeling creativity, and the use of vision to guide work. It is worth noting that the core of the Reggio approach is the artist, the atelierista. Perhaps, more than we realize yet, the way the artist moves in the classroom, sees beauty in the most mundane materials, and creates beauty from the everyday is responsible for the most significant effect on the children. Reverence, respect and passion for creativity cannot be taught through words – this must be taught through the senses, the body, the creative mind at work.

In summary, fostering creativity requires teaching the intricacies of the creative process, modeling creativity, and the use of vision to guide work. It is worth noting that the core of the Reggio approach is the artist, the atelierista. Perhaps, more than we realize yet, the way the artist moves in the classroom, sees beauty in the most mundane materials, and creates beauty from the everyday is responsible for the most significant effect on the children. Reverence, respect and passion for creativity cannot be taught through words – this must be taught through the senses, the body, the creative mind at work.

I invite you to end by listening to the illuminated poem The Hundred Languages of Children, and investigating the traveling exhibit of the Reggio Emila preschools. Please let me know your thoughts, ideas and impressions.

References

Howard-Jones, P. A. (2008) Fostering creative thinking: co-constructed insights from neuroscience and education. Bristol: Higher Education Academy, Education subject center.

Howard-Jones, P. A., Blakemore, S.J., Samuel, E., Summers, I.R., & Claxton, G. (2005). Semantic divergence and creative story generation: an fMRI investigation, Cognitive Brain Research, 25, 240-250.

Howard-Jones, P.A., Taylor, J., and Sutton, L. (2002). The Effects of play on the creativity of young children. Early Child Development and Care, 172 (4), 323-328.

Howard-Jones, P.A. (2002). A dual-state model of creative cognition for supporting strategies that foster creativity in the classroom, International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 12 (3), 215-226.

Rizzolati, G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., and Gallese, V. (2002). From mirror neurons to imitation: Facts and speculations. In A.N. Meltzoff & W. Prinz (Eds), The imitative mind: Development, evolution and brain bases. Cambridge studies in cognitive perceptual development (pp. 247-66). New York, Cambridge University Press.

While every household has their own way, washing the hands upon arriving home is the proven way to keep germs out. Most sicknesses enter our homes on our hands and good old fashioned soap and warm water is still the best way to prevent the spread. A simple handwashing station by the door includes a basin and pitcher, soap and paper towels. While your child puts away their shoes you can fill the pitcher with warm water and model how to wash hands together. This is especially useful for playdates with other parents and children!

While every household has their own way, washing the hands upon arriving home is the proven way to keep germs out. Most sicknesses enter our homes on our hands and good old fashioned soap and warm water is still the best way to prevent the spread. A simple handwashing station by the door includes a basin and pitcher, soap and paper towels. While your child puts away their shoes you can fill the pitcher with warm water and model how to wash hands together. This is especially useful for playdates with other parents and children!

Finally, I can’t say enough about simply finding a spare drawer, cabinet or shelves in every room to place a revolving hands-on activity. This allows for simple redirection to safe and purposeful activity wherever you and your child might be at home!

Finally, I can’t say enough about simply finding a spare drawer, cabinet or shelves in every room to place a revolving hands-on activity. This allows for simple redirection to safe and purposeful activity wherever you and your child might be at home!

These Sensorial Scent Jars were made from large salt and pepper shakers. They can be filled with a variety of smells using spices, herbs, or essential oils on cotton balls. One summer we did vanilla, strawberry and chocolate as an ode to ice cream!

These Sensorial Scent Jars were made from large salt and pepper shakers. They can be filled with a variety of smells using spices, herbs, or essential oils on cotton balls. One summer we did vanilla, strawberry and chocolate as an ode to ice cream!

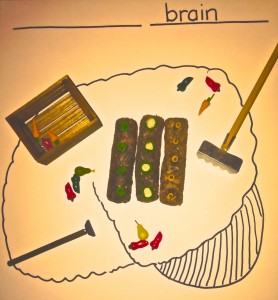

This Practical Life work, Chopstick Placing, gave new life to colorful chopsticks that had lost their partners and an old soap dispenser with a top that stuck. This task works grapho-motor skills as children try to insert the pointed end into an increasingly smaller hole.

This Practical Life work, Chopstick Placing, gave new life to colorful chopsticks that had lost their partners and an old soap dispenser with a top that stuck. This task works grapho-motor skills as children try to insert the pointed end into an increasingly smaller hole. This Practical Life work, Yarn Pulling, was created by the teacher of our Montessori From the Start Playgroup who also happened to be a fiber artist. Children loved pulling the different textured yarn as far as it would go. The yarn was threaded through the holes and knotted so that that turning the box provided never-ending opportunities to pull.

This Practical Life work, Yarn Pulling, was created by the teacher of our Montessori From the Start Playgroup who also happened to be a fiber artist. Children loved pulling the different textured yarn as far as it would go. The yarn was threaded through the holes and knotted so that that turning the box provided never-ending opportunities to pull.

Children in the 15 – 24 month range are in the naming stage of language. Simple word books are favorites and vehicles were all the rage in our home. This Language Work, Vehicle Matching was made by photocopying, cutting and laminating pages of a book. Naming and matching are important stages of language learning in Montessori and lay important foundations for expressive language and symbol identification.

Children in the 15 – 24 month range are in the naming stage of language. Simple word books are favorites and vehicles were all the rage in our home. This Language Work, Vehicle Matching was made by photocopying, cutting and laminating pages of a book. Naming and matching are important stages of language learning in Montessori and lay important foundations for expressive language and symbol identification.

Email neuleaph@gmail.com to learn more!

Email neuleaph@gmail.com to learn more!

home that she had risen to new levels of maturity and calm. Over the slide from spring to summer we saw her find her place in our classroom community. Put down roots. Blossom.

home that she had risen to new levels of maturity and calm. Over the slide from spring to summer we saw her find her place in our classroom community. Put down roots. Blossom.

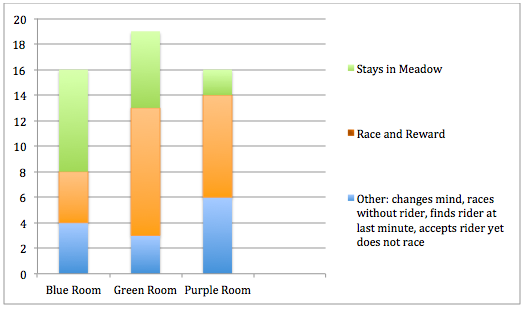

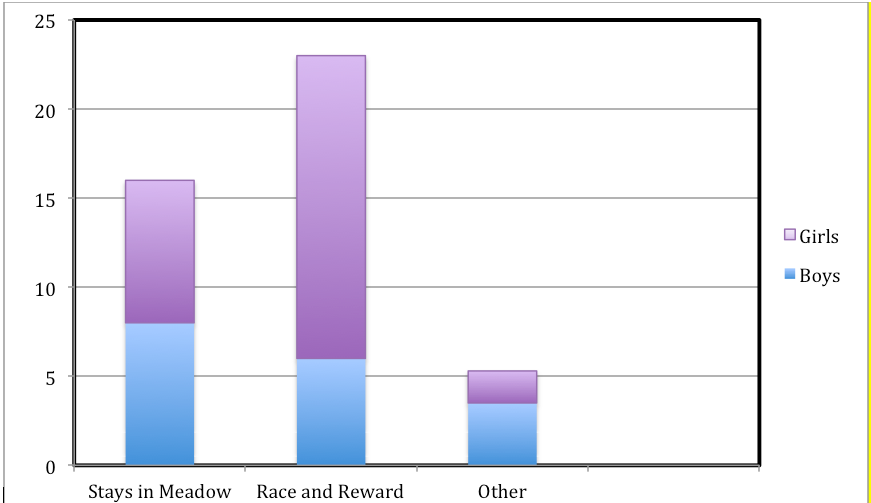

The project really took shape when I attended a Learning and The Brain conference at Columbia University on Student Mindset and Motivation that spring and heard Heidi Grant Halvorson speak. Her research, described in her book

The project really took shape when I attended a Learning and The Brain conference at Columbia University on Student Mindset and Motivation that spring and heard Heidi Grant Halvorson speak. Her research, described in her book  I set out through all of the classrooms, carrying a picture of a little horse and a story:

I set out through all of the classrooms, carrying a picture of a little horse and a story: