My life has been filled with music from the start. As a young child, music played a major role in our household. My mother is a passionate musician herself and has taught music to children for as long as I have been alive. As early as I can remember I was moving and clapping to Kodaly folk songs in her music classes, singing in her choir and practicing for long hours, my sister and I on our flutes while she accompanied on the piano. Many nights I drifted to sleep with the vibrant chords of a piano sonata drifting up the stairs. Music was not just a pastime. My mother passed on the conviction that being able to connect to music, to develop musical skill, to use music to express oneself – these were vital pieces of a full and healthy life.

My life has been filled with music from the start. As a young child, music played a major role in our household. My mother is a passionate musician herself and has taught music to children for as long as I have been alive. As early as I can remember I was moving and clapping to Kodaly folk songs in her music classes, singing in her choir and practicing for long hours, my sister and I on our flutes while she accompanied on the piano. Many nights I drifted to sleep with the vibrant chords of a piano sonata drifting up the stairs. Music was not just a pastime. My mother passed on the conviction that being able to connect to music, to develop musical skill, to use music to express oneself – these were vital pieces of a full and healthy life.

My interest in music and the brain began five years ago when I was given the task of developing and teaching the music curriculum for the Red Hook Playgroup, the progressive Montessori-based preschool I helped found in 2007. As a student of Neuroscience and Education, I turned to the exciting new literature that was emerging on music and the brain. I was fascinated to discover the links between recent research findings and the time-honored music education methods I chose as the foundation for my own teaching, namely Kodaly, Dalcroze and Orff.

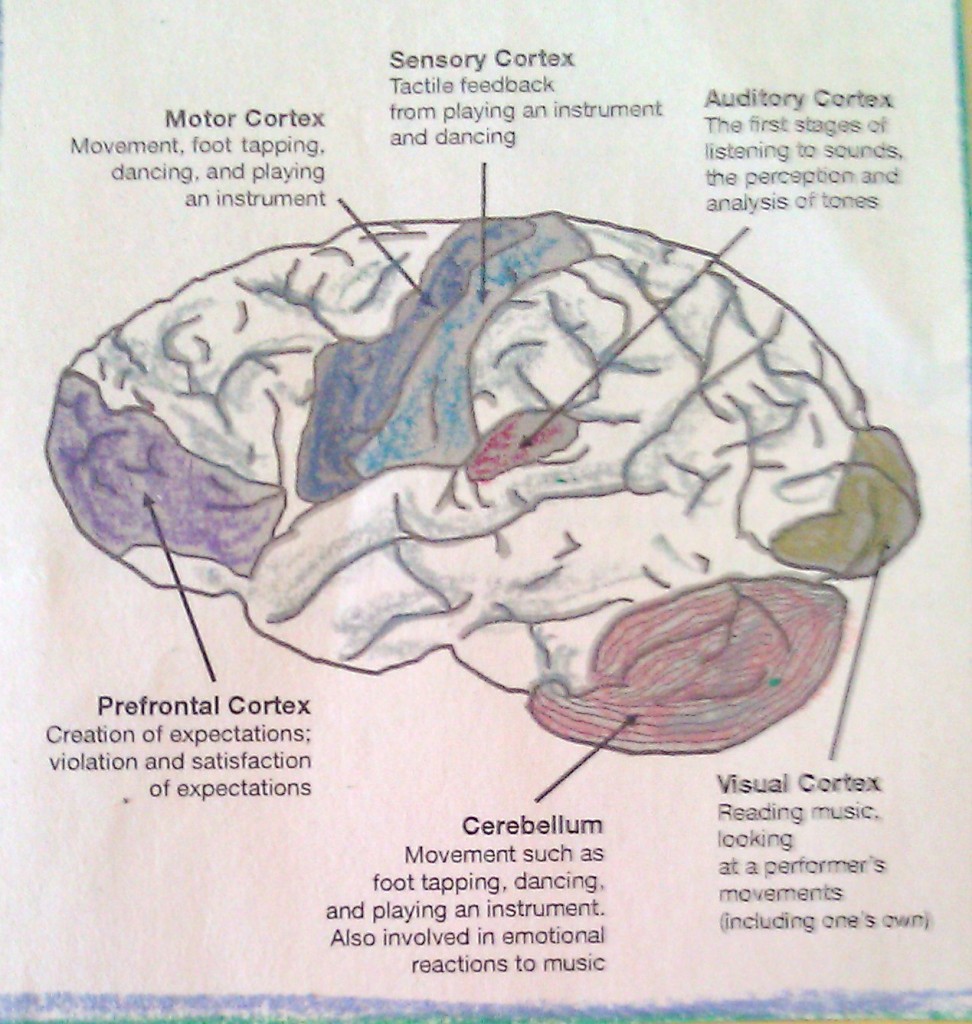

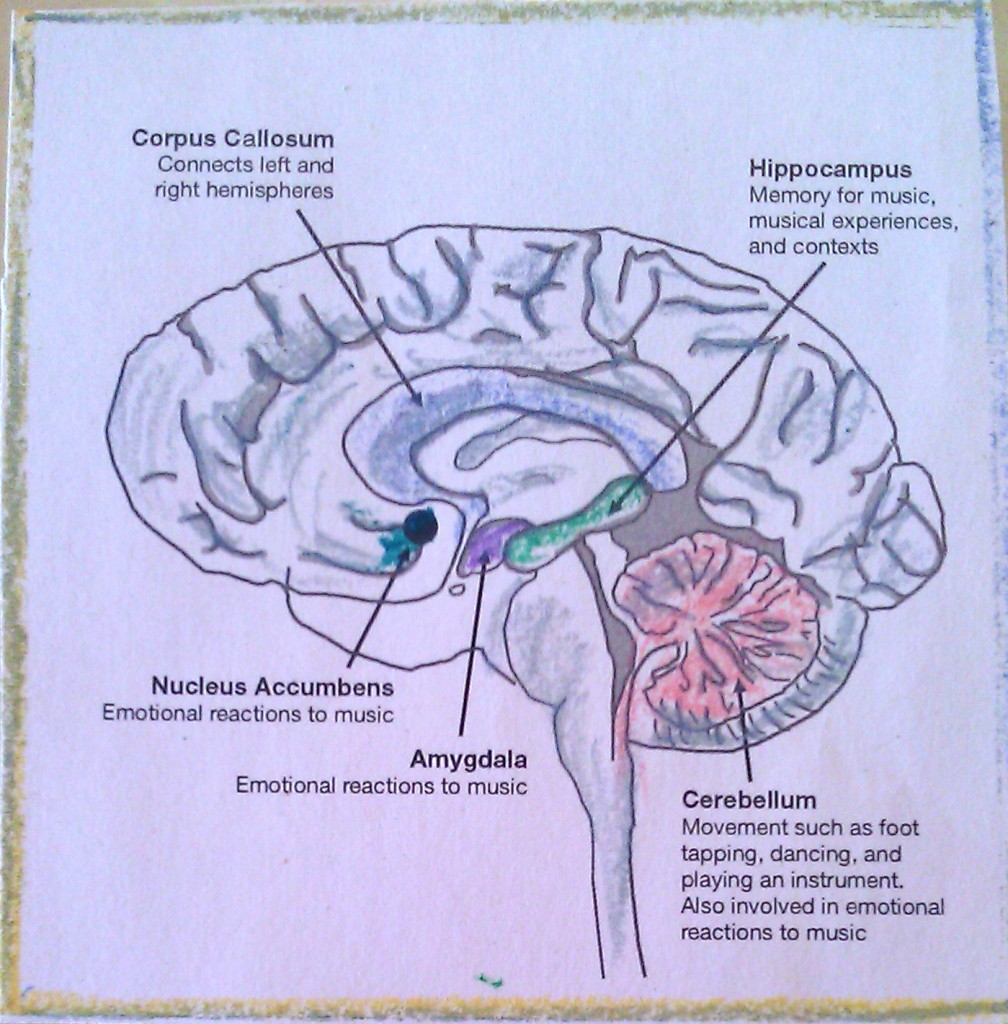

The pictures above and below were adapted from the Appendix of Daniel Levitin’s This is Your Brain on Music: The Science of A Human Obsession (2006). Clearly, music involves areas all over the brain. As Levitin points out in his book, it is not the specific areas that matter as much as the countless connections between them that music ties together.

According to Levitin, the fields of cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience have debated the purpose of music for the developing brain. The latest research shows that music is not just an “evolutionary accident,” but is very important for childrens’ cognitive development. On the other hand, these benefits of music for the child’s brain are not achieved by simply listening to music – the so-called “Mozart Effect” that sold millions of specially advertised childrens’ cd’s and Baby Mozart dvd’s. Rather, children must be active musically – moving to beat and rhythm, singing songs, learning to read, play, and ultimately make music. As Levitin states, “Music for the developing brain is a form of play, an exercise that invokes higher-level integrative processes that nurture exploratory competence…” Like any kind of childrens’ play, it is coming to be recognized as integral to a child’s early experience.

According to Levitin, the fields of cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience have debated the purpose of music for the developing brain. The latest research shows that music is not just an “evolutionary accident,” but is very important for childrens’ cognitive development. On the other hand, these benefits of music for the child’s brain are not achieved by simply listening to music – the so-called “Mozart Effect” that sold millions of specially advertised childrens’ cd’s and Baby Mozart dvd’s. Rather, children must be active musically – moving to beat and rhythm, singing songs, learning to read, play, and ultimately make music. As Levitin states, “Music for the developing brain is a form of play, an exercise that invokes higher-level integrative processes that nurture exploratory competence…” Like any kind of childrens’ play, it is coming to be recognized as integral to a child’s early experience.

One of the specific benefits that has received attention in the field of cognitive and educational neuroscience lately is the connection between music and language development in young children. In neuroscientist Aniruddh Patel’s recent book Music, Language and the Brain, (2008), he outlines a detailed body of research that shows language and music to be intrinsically linked in that both involve “complex and meaningful sound sequences” that “define us as human.” Neuroscientists have long known that music and language reside in corresponding regions in the Left and Right hemispheres respectively, at least for most right-handed individuals. Cognitive scientists, developmental psychologists and educators alike know the powerful role that language plays in cognitive development. Patel argues that music serves a similar role.

I would like to explore this idea from the standpoint of early childhood music education. As I mentioned above, my curriculum draws deeply on three widely respected approaches that share the conviction that fostering musical creativity should be valued above all else, namely Emile Dalcroze, Zoltan Kodaly and Carl Orff. Please be inspired to research these men and their approaches more thoroughly – it is all amazing work.

For the sake of simplicity, I am going to provide a snapshot of what the influence of these three approaches looks like in a preschool classroom, with the music curriculum I have developed as an example. The point of interest for me is the way that these models of high quality music education lend support to the important connections between music and language.

Dalcroze Eurythmics

Eurythmics means “good rhythm.” In accordance with the approach of Emile Dalcroze and early childhood music educators such as Monica Dale, children learn music best by moving to it. My youngest students begin music training at two or three, and the first year focuses largely on developing a keen sense of beat and rhythm, tempo and dynamics, timbre and musical expression – all by moving their bodies. We explore our own heartbeat, our walking beat, clapping beat, and stomping beat. Through exercises, games and stories we learn to express increasingly complex rhythms with choreographed movements. The music the children move to is simple, played on a range of instruments before their eyes, and can be carefully adapted to their movements. This week my two-year-olds were moving as drifting autumn leaves in time to a breezy song played on the octave bell and ridged rhythm sticks, or hopping and bouncing like acorns up and down the C-major scale along with a two-tone drum.

Brain imaging has revealed that during these activities child’s motor, sensory, and auditory areas of the cortex are all fully active. A young student’s cerebellum is also highly engaged in both executing movements and processing the emotional context or meaning of the music.

The idea that spoken language is deeply grounded in body movement is becoming more widely accepted and understood. Early concrete sensory and motor experiences are known to be key for developing the symbolic and abstract thinking necessary for strong language skills later in development. An article I co-authored for Developmental Neuropscyhology (2002) during my undergraduate neuroscience studies titled Putting Language Back in the Body discussed the ways that spoken language and gesture are inseparable throughout the development of language in the brain. (Clicking will bring you to Neuroeducation Services where the article is listed with other examples of my work at the bottom of the page). In this way, music can be seen as embodied cognitive play, strengthening these sensory and motor pathways and increasing brain connections for fine-tuned and healthy functioning.

Orff

Carl Orff brought the now ubiquitous xylophone and glockenspiel into the early childhood classroom, and with it provided a way for the experience of music to be made truly accessible to the young child. Seated in a circle on the rug around a teacher, children in my program watch and listen to the simple octave bell, pentatonic chimes, or chromatic glockenspiel during every class. Their knowledge builds between ages two and five, beginning with a basic familiarity with the notes, scales and intervals that are central to the music of our culture. In music classes this week we began finding notes on the scale before singing songs that use them, naming them (Sol, Mi and La…ring any bells?), and holding these pitches in our mind. We will soon begin using our ears alone, with eyes closed (“No peeking!), to recognize and name these notes

By the third year, children are listening to the differences between scales and keys on more complex Orff instruments, such as the chromatic glockenspiel, and practice deciding if these sound “right” or “wrong” to their ears. At the same time they are practicing playing simple songs and scales, supported by removing and replacing keys.

Through brain imaging we know that areas all over the cortex, particularly in the right, or non-language, hemisphere (excluding some left-handed individuals) are active during these tasks. The auditory cortex processes the sounds, the visual cortex sees the mallet strike the notes and move in space. According to research pioneered by Kohler et al (2002), motor planning areas responsible for preparing the hands for the gross and fine motor movements involved in playing the octave bell even light up for children watching and listening to another person play the instrument. The prefrontal cortex is at work creating expectations and evaluating if the music streaming in matches or violates these expectations. Finally, the amygdala and nucleus accumbens allow music to produce true emotional reactions within a listener’s mind and body, imbuing music with rich meaning.

Throughout his book, Patel (2008) points out the close matches between language and music. Beginning at birth babies brains become tuned to the specific speech sounds of their first language. The phonemes “r” and “l” have many aspects in common, but an English speaking child can distinguish between them easily. A Mandarin Chinese child on the other hand loses this ability very early, never to return – unless they hear English from the start. In much the same way, a child’s auditory cortex is shaped by listening to, distinguishing between and naming single notes. The notes common to their culture are a musical alphabet.

Patel goes on to show that notes are put together into patterns, and chords to create meaning and communicate ideas, the same way that isolated speech sounds become words. This involves a complex interplay between a young brain’s expectations based on experience, and what she hears with her ears. From the beginning, children in my program are listening to and learning to tell stories with the octave. High and low, soft and loud, fast and slow, gently falling, bouncing, or stopping – the notes tell tales of skittish squirrels or scampering monkeys, they become happy or sad, they swim, dance, slide and scurry. In this way they are truly using music as an active language.

Kodaly

Being able to read music fluidly and accurately is a skill that most musicians master. While many musicians do play by ear, the ability to read music allows for an amazing feat in my opinion: the ability to pick up and play a piece having never heard it before. Musical literacy opens up the world to a musician, allowing music written long ago to be reborn at his fingers. Children trained in the Kodaly technique are learning this skill before they learn to read words.

Starting in their second year, children begin to learn the symbols for the units of beat and rhythm they have become so familiar with through moving, clapping, stomping, dancing and playing percussive instruments. Once “ta,” “ti-ti,” “tum” and “too” enter the scene, children are speaking rhythm. Simple lines and dots become symbols for these units of rhythm. We begin by pretending we are the first musicians in the world -and to show the music in our minds we draw beats with sticks in the sand. Then we are off, cutting up beats for “beat soup,” laying out “ti-ti’s” and “ta’s” into felt squares, or turning a “ti-ti” into a “tim-ka” by adding weighing down one side with a ball, and lightening the other with a tiny wing.

By the end of their third year children are learning to compose, record and play their own rhythms and classmate’s rhythms. By moving and playing their way through musical stories, such as the long journey of a thirsty elephant herd, a pack of wolves on a hunt, or dolphins who dance, they learn to match and assemble written beats, rhythms and rhythmic phrases to “write” the story on their own.

The act of reading involves extensive and strong connections between many parts of the brain: visual, language, motor, and prefrontal regions coordinate with memory and attention to execute the complex task of merging patterns of sound intimately with written symbols to communicate abstract ideas.

Few children in our culture are learning to read music by age three and four, though I believe any early childhood teacher could draw their own connections between the skills developed by this musical ability and written literacy. It is remarkable to watch a three year old stop his spoon in mid air upon arriving at a rest while playing Peas Porridge on a metal pot. It is inspiring to witness a four-year old’s smile of satisfaction as she moves back and forth between playing steady and syncopated rhythms while her eyes move between the cards.

To teach music mindfully means to understand how to forge the myriad connections throughout the brain that allow music to come alive and raise its voice, to move a child in powerful ways, to put her in touch with something wondrous.

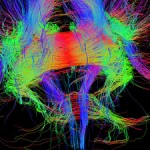

Using a cutting edge technique called diffusion tensor imaging, this image (Human Brain Connections by Ethan Hein) leaves us with a vivid picture of the connections between the many brain areas that music invites into action.

Using a cutting edge technique called diffusion tensor imaging, this image (Human Brain Connections by Ethan Hein) leaves us with a vivid picture of the connections between the many brain areas that music invites into action.

Please click the pics to explore some of the latest research and ideas on music and the brain. I would love you know your thoughts.

Please click the pics to explore some of the latest research and ideas on music and the brain. I would love you know your thoughts.

References

Levitin, D.J. (2006). This is your brain on music: The science of a human obsession. New York: Penguin.

Kelly, S. D., Iverson, J. M., Terranova, J., Niego, J., Hopkins, M., and Goldsmith, L. (2002). Putting language back in the body: speech and gesture on three developmental time frames. Developmental Neurospychology, 22(1), 323-349.

Kohler, E., Keysers, C., Umiltà, M.A., Fogassi, L., Gallese, V. and Rizzolatti, G. (2002) Hearing sounds, understanding actions: action representation in mirror neurons. Science, 297, 846-848.

Patel, A. D. (2008). Music, Language, and the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press.