The story of the Little Horse was a project that I conducted with all three classrooms at the Red Hook Playgroup in the spring of 2013, as part of my work as the Developmental Support teacher.

It all began with a little girl in the Blue Room, our 2’s classroom. I will call her Tess. From the start of the year she had been a bit of a puzzle to us. Curiosity shone behind her deep brown eyes and yet she shied away when a teacher approached her mat to ask about how she was exploring her materials. In response to questions about her stack of cubes she might topple it and scatter them.

As we made our way to mid-year, Tess became a topic at our Developmental Support meetings. While other young students settled, as they tended to do in our open-choice classroom, on a repertoire of work that both challenged and satisfied them, Tess seemed to confine herself to activities that were too easy. She might spend whole mornings with the same tinte blocks, even after her interest had clearly waned, refusing invitations to join other work or try something new. We could see her interest in the work around her and yet she grew quickly frustrated when her first attempt to replicate something her peers were doing failed. She would give up, resisting help and becoming restless and distracted.

It was my role to spend time observing and working with Tess closely in search of the hidden hinge that would open her up, motivate her and put her in touch with the environment – our third teacher – in way that would ignite natural engagement. I invited teachers to pose questions, and to look over Tess’s artwork, stories, notes from her free play, looking for clues to why she was not motivated the same way that her peers were – and how we could find a way to change that.

The image of a horse came up over and over in Tess’s work. She drew horses, she wrote stories about them, she liked to pretend she was a spirited horse on the playground and in the classroom, tossing her head and kicking her feet, often kicking off her shoes. When asked to sit at the edge of the rug, she would prance sassily to the center of the circle and rake the rug with her hands. And, like a spirited horse who refused the saddle, Tess made it clear that rewards and praise were simply not going to work to motivate her. She was trying to tell us something about herself through her behavior. Thus Tess was the primary inspiration for the story of The Little Horse.

The project really took shape when I attended a Learning and The Brain conference at Columbia University on Student Mindset and Motivation that spring and heard Heidi Grant Halvorson speak. Her research, described in her book Focus: Use Different Ways of Seeing The World for Success and Influence, explored a different mindset framework: a promotion focus versus a prevention focus.

The project really took shape when I attended a Learning and The Brain conference at Columbia University on Student Mindset and Motivation that spring and heard Heidi Grant Halvorson speak. Her research, described in her book Focus: Use Different Ways of Seeing The World for Success and Influence, explored a different mindset framework: a promotion focus versus a prevention focus.

Promotion-focused people tend to see goals as opportunities go gain something. They have lofty aspirations and are willing to take risks to achieve grand objectives. They seek positive feedback and can become deflated without it.

Prevention-focused people on the other hand tend to think about goals in terms of what they might lose if they don’t achieve their objectives. They tend to try to avoid mistakes and losses. They can be uncomfortable with praise or optimism and feel worried or anxious when things go wrong.

Unlike Carol Dweck’s Fixed/Growth Mindset model, this framework represents a spectrum on which people fall but neither end is seen as better or worse. These mindsets are shaped by early life experiences and become part of who we are and how we approach challenge. Both can be used as strengths – but often classrooms are polarized toward the classic promotion mindset.

I began considering this in light of Tess. These dual mindsets certainly seemed like an important factor to consider when something wasn’t clicking with a student in the classroom. How might I assess where children were on this mindset scale?

I set out through all of the classrooms, carrying a picture of a little horse and a story:

I set out through all of the classrooms, carrying a picture of a little horse and a story:

This story is about a little horse who goes to school. Since she is a little horse, instead of going to school in a classroom she goes to school in a meadow. Instead of learning letters and numbers she learns to wear and saddle and let people ride on her back.

This morning, like many mornings, she is down by the river with her teachers because she ran away from the others. She doesn’t want to wear a saddle or let people rider on her back. She wants to play and run free in the meadow.

Her teacher says, “Little horse, I have something important to tell you. The people who live in the house on the hill have been watching all of the horses at school. They have told me that you are the fastest and strongest out of all the horses. They said that if you can learn to wear a saddle and let people ride on your back you could be one of the special horses that can become a race horse. They think that you might even win a race on day, and be a famous race horse.”

I asked each child in the school to tell me what they thought the Little Horse should do.

My questions were: What directions would this story take? How would younger children answer differently than older children? And finally, How would different developing mindsets (promotion vs prevention) be represented in children’s answers?

The results were fascinating.

Childrens’ stories school wide settled in categories, most falling into two conditions I called Stay in the Meadow and Rider, Race, Reward. They identified with the Little Horse, and had very clear ideas about what he or she should do. Some children had the Little Horse taking on the challenge of learning to accept a rider in order to reach the reward. Others had no interest and were happy to stay in the meadow.

Tess’s story read:

No, she doesn’t want to be a racehorse. She wants to be free and run in the meadow. ‘No, N. O. No. You have to learn to steer people on your back.” She’s not going to listen. She stays in the meadow until she’s big!

Needless to say, she lined up with a prevention mindset.

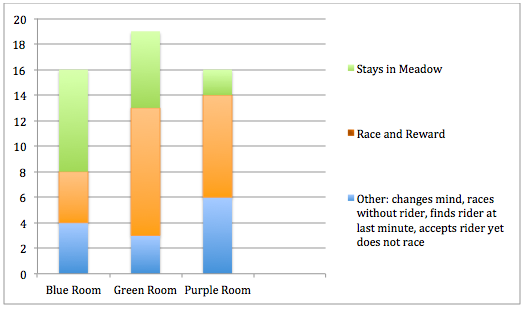

The chart below represents the effect of children’s ages on the mindset represented in their stories. Blue Room children were 2.5 to 3, Green Room 3 to 4 and Purple Room, 4 to 5. Certain trends are apparent. The number of children who chose to have the Little Horse stay in the meadow falls as children mature. The number of children who chose to have the Little Horse accept a rider, race and win the reward swells in the 3’s classroom, and then falls a bit in the 4’s/5’s as independent thinking introduces unique outcomes, which were more complex and nuanced. These outlier stories were fascinating in and of themselves, though this is a topic for another post.

Mindset Stories by Age Group

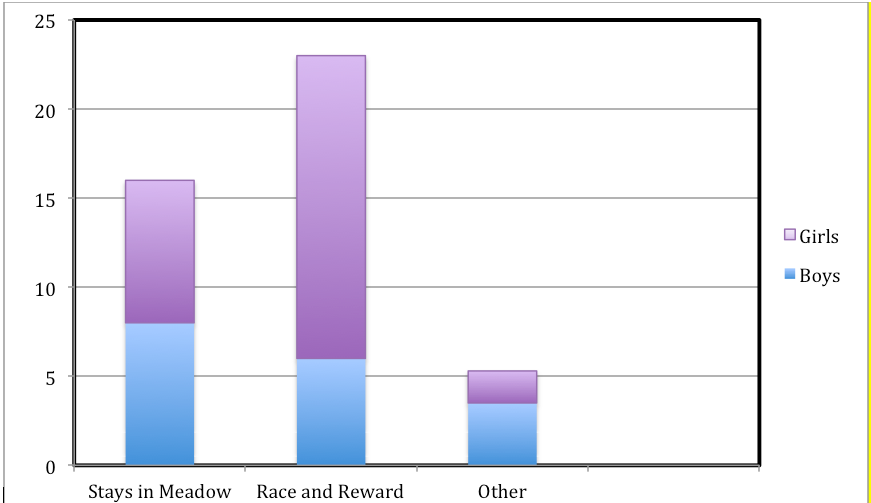

Mindset Stories by Gender

Another interesting trend that emerged school wide was the gender split for the Race and Reward category. As many teachers know, boys as a group pose their own challenges when it comes to engagement, motivation, attention and behavior. Especially in early childhood, “boy energy” is often seen as an obstacle to a well-executed lesson plan. It is easy to see here that, while there is a half-and-half divide for the Stays in the Meadow Category, Girls chose Race and Reward two to one over boys.

Is it possible that we as teachers are missing an opportunity when we do not consider a child’s mindset? How can my findings from this project be applied to the classroom?

I welcome your comments!

Check back for the next post in this series which will explore the idea of mindset stories in more depth.